In my previous post I used a pump and bicycle to explain the importance of understanding a problem, before blaming the tool for failing to fix it.

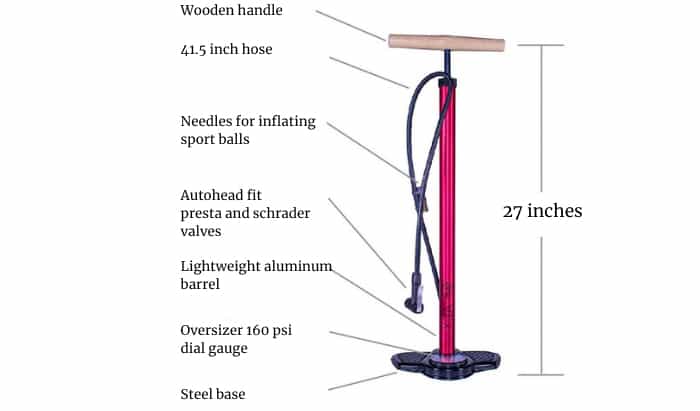

Now imagine the same bicycle pump, and observe its parts: a metal cylinder, a metal rod, metal disk with rubber lining, a nozzle, a valve and a wooden bar.

All these parts are designed and aligned in such a way that the pump can fulfill its purpose: pushing air into the bicycle tire. All works well, until the pump ages over time and parts start to degrade. Metal rusts, rubber degrades and wood rots. All can cause the pump to lose its function; it can no longer fulfill its purpose. Chances are that you’ll notice its loss of function when pushing the wooden bar down. It no longer pushes back. And even worse, the tire isn’t inflating anymore. But the wooden handle is fine. And so is the metal rod that it is attached to. It’s still there. You instinctively know that replacing the handle or metal rod is not going to fix the problem. Upon closer inspection you find out that the rubber lining of the metal disc inside the cylinder has deteriorated and air that is no longer getting compressed. What we take for granted is that the problem manifested itself in a different place (at the wooden handle) then where we had to fix it (at the rubber lined metal disc). We don’t give it a second worth of thought. We’re wise enough to inspect the entire system and end up replacing the broken parts.

Now imagine a bit of an absurd situation where we take a much more local approach to fixing this problem with the bicycle pump. Let’s say the person experiencing the problem can think no further than the place where he experiences the problem: at the wooden handle. As a remedy the cyclist replaces the wooden handle. No improvement. At best, this leaves the performance of the pump unchanged. It doesn’t improve, but it doesn’t worsen either. When systems like the pump are simple and predictable in behavior you’ll run less of a chance of making things worse with fixes in the wrong place. Fortunately, we’re wiser than this, and look beyond the handle to fix the problem. You might be surprised though, that this wisdom doesn’t extrapolate to trying to fix problems in all kinds of systems.

Let’s make a jump to something a tad more challenging: organizations. Organizations are complex social systems made up of people and their interactions. An organization fulfills its purpose by organizing these people and their interactions in a way that it is most likely to do so. Because the “parts” of these systems are purposeful, the resulting organizations will be purposeful as well. This causes such systems to be immensely more complex than something simple like a bicycle pump. Here, the effects of changes or fixes in the wrong place are equally more unpredictable as a result.

So you would expect people to apply the same wisdom in solving problems in an organization as we do in more simple systems: consider that the source of a problem might not be in the place where we experience it. Right? Helas. We usually don’t.

Unlike the systemic approach of solving the problem with the bicycle pump, we take a much more local approach to solving problems in organizations. For example, pressuring a team that is delivering features at a lower rate than expected, to just work harder, is like replacing the handle of a bicycle pump with a leaking valve and expect it to work again. Even if you’re not the kind of person that puts unnecessary pressure on teams, you’ve probably experienced fixes that backfired, or problems that became increasingly more difficult to fix over time, because you kept falling for what you thought was the quick fix. We do this, because we fail to understand that the symptom of a problem is not the same as the source of a problem.

“Over 90% of the problems that arise in organizations are better solved somewhere else than where they appear.” – Russel L. Ackoff

Dealing with problems in an organization requires a systemic approach. This means that you need to identify all parts of the system that are needed to fulfill the function that is broken. You need to find and understand its interactions, so that you can uncover the areas where the performance of one part negatively affects the performance of another, causing the system to lose its function. So it may seem that you’ve solved the problem, but if it’s in the wrong place, it will probably return bigger and uglier. If you succeed in finding the source of a problem, you have a better chance of actually resolving the problem: changing the system so that it is less probable to reoccur.

And this is where building an agile organization and systems thinking go hand in hand. You can inspect and adapt all you want, but if your adaptations are like replacing the pump handle, don’t bother inspecting at all. You’ll only make things worse.

No comment yet, add your voice below!